The Squirrel Strikes Back: Analysis of the newly emerged cobalt-strike loader “SquirrelWaffle”

Since early-mid of September 2021, a new malware loader dubbed “Squirrelwaffle” has been discovered and observed delivering the attack framework Cobalt-Strike.

In the recent cybercrime landscape, several prolific malware has either gone or been less observed. This newly created gap gives opportunities for the birth of a new malware such as Squirrelwaffle to fill the hole that others left.

In this article, I will present an analysis of this new threat. Similar to most of my malware analysis articles, the article will be a mix between a presentation and a step by step dynamic or static analysis, with an emphasis on SquirrelWaffle download capabilities.

The dropper

In terms of the initial attack vector, the malware is being delivered by classic phishing documents and continues with dropping .vbs files and launching Powershell.

The initial access phase ends with an executable dropper being downloaded to the infected machine.

The dropper is a 32-bit DLL file, which also packed with a custom crypter.

Furthermore, the dropper has 8 export functions in addition to the DllEntryPoint one. This tactic was also observed in Ursnif’s dropper, which has been observed having a large number of export functions.

Usually, the reason for that is to slow down analysis.

Unpacking mechanism

To manually unpack this sample, and also observe the interesting parts of the unpacking mechanism we’ll do the following:

First, we’ll set a breakpoint on VirtualAlloc and hit Run, once we reach the first breakpoint, click “Return to user code” or “execute till return + step over”.

Now we can observe the following:

- Call to ebx+2113E4 - which is the call to VirtualAlloc

- rep movsb -which will write shellcode to the newly allocated memory

- jmp eax - execute the shellcode instructions

Because the shellcode is stored in the EAX register, we can observe it if we’ll click “follow in dump” on the EAX register. we can see the bytes E8 00 00 00 00 which is a classic trick shellcode uses to obtain the next instructions.

From this behavior, we can also assume that the entire unpacking mechanism will occur within the context of a shellcode.

Next, click Run twice until we’ll reach the third instance of VirtualAlloc. After reaching it do the following:

- Click “execute til return” + “step over”

- Go to the EAX register and click “follow in dump”

- Set a write hardware breakpoint on the first bytes of the newly allocated memory buffer.

After setting the breakpoint, click Run three times. We’ll notice that the buffer inside the allocated memory will be filled with content.

When reaching the third Run, we’ll find ourselves in a small loop with some classic opcodes that we expect to see in unpacking loops such as rotate right and exclusion or (ror and xor opcodes) .

In fact, this specific loop, and the majority of this crypter were observed during the last two years in other malware droppers, such as: Ursnif, Zloader, and Hancitor.

By setting a breakpoint on the leave opcode we can go to the place where the loop ends. Once we did it, we can see the ASCII characters M8Z which indicates an APLIB compression.

Now that we know that this content is compressed with APLIB, the most logical thing to expect is a decompressing mechanism.

To observe this mechanism do the following:

- Remove the write hardware breakpoint from the buffer

- Set a new Access hardware breakpoint on the first bytes of the APLIB header.

- Click Run

After clicking Run, we found ourselves in a loop that consists of several functions, this loop will be the one that decompresses the APLIB content.

In terms of decompression location, this mechanism works in the following way:

- It will get bytes from the beginning of the APLIB content, manipulate them, and will store them in the ESI register.

- It will copy the decoded content at offset 7040, the offset where the content will be written will be stored in the EDI register.

To skip the entire unpacking and decompressing process, in the loop, we can scroll down, and we’ll see three ret opcodes, set a breakpoint on the third one, and hit Run.

Now, follow in dump in the EDI register where we know the unpacked content should be stored. We can see now the MZ header and the unpacked SquirrelWaffle malware.

To dump it, we can mark the entire content from the MZ header until the end and save it as binary using the xdbg, or just use the pe-sieve tool.

SquirrelWaffle

Similar to the dropper, SquirrelWaffle is also a 32-bit DLL file.

In contrast to the dropper, this DLL file has only one export function called “ldr”. Also, it seems that the file itself is has a DLL name in it called “Dll1.dll”. This fixed name of a DLL file was also observed in Qbot (stager_1.dll), Trickbot(templ.dll), and IcedID (loader_64_dll.dll).

When we investigate statically the malware from the “ldr” export function, we can see that the function invokes only one very long and nested function. For this analysis, and to make tracking the article more easier, we’ll labeled it as “the core function”.

The function starts with the malware attempt to get the environment variables of the APPDATA and TEMP directories.

However, some of the malware functions are not easily understandable, and some deal with content decryption. To verify it, we need to investigate dynamically.

To do so, we’ll need to start from the “ldr” export function, there are two ways to reach it.

First way

The first way will be to start the Xdbg with loading Rundll32 and assign the malware path with the ldr export function as an argument. (In my analysis I called the unpacked file “time.dll”)

However, I sometimes found this method not reliable, and the DLL file often goes to the DllEntryPoint function instead.

Second way

The second route is a cool memory trick, that will work as the following:

- we’ll first go to the DllEntryPoint

- We already know from the first glance of static investigation that the ldr function should start with getenv() function that searched the APPDATA and TEMP environment variables.

- Because the APPDATA and TEMP strings are hardcoded in the malware we’ll search for their location.

- we’ll direct our malware execution flow to go directly to the location of the function that the APPDATA and TEMP are found.

Getting the location of the APPDATA & TEMP function

To do so, once we are in the DllEntryPoint, do:

- Right click

- Search for

- Current region

- String references

Now, we found ourselves with the entire list of the hardcoded strings of the malware, there we can also see our APPDATA & TEMP strings. let's click on one of them.

Once we click, we can see the places where the APPDATA and getenv() function will be executed, this is also the function that the ldr export function calls aka the core function.

This is the place we want to start our dynamic investigation, and therefore, we would want to direct the malware to start at the beginning of this function.

Changing the malware execution flow

To change the direction of the malware to start in this function, do the following:

- Right click on the first function line of code

- Copy

- Address

Now, at the right side of the debugger, you can see the EIP register which is responsible for holding the next instruction to be executed, we’ll want to manipulate it.

To do so, do the following:

- Right-click on the EIP register

- Modify value

- In the Expression box, paste the address you copied.

- Click OK

After clicking OK we can see that the instruction pointer was changed to the start of the core function, now our dynamic analysis can be performed.

Core function

As mentioned, the ldr export function leads us to one specific big function which we call “the core function.

This function will have several objectives and will also call to other functions that will take part in this malware download mechanism.

Observable functions

Before digging into the more challenging functions, let's talk about the more visible API calls that this function consists of.

The majority of these functions are aimed to collect information about the infected machine.

As already mentioned, the malware attempt to collect information about the environment variables c:\users\user\appdata\roaming and c:\users\user\appdata\local\temp using the getenv() function.

The malware also attempts to collect the name of the local computer using the GetComputerNameW() function.

The malware then attempts to get the machine’s user name using the GetUserNameW() function.

The malware will extract information about the configuration of a workstation using the function NetWkstaGetInfo().

Maintenance functions

As we enter the malware’s core function, we observe a function named “sub_10006A20” (name can change with other instances) that will repeat itself multiple times during the malware’s execution.

This function receives three arguments, two pointers, and a length, the function will copy the data from one pointer and assign it to another.

For example, in the first iteration, we can see sub_10006A20 do the following:

- gets the pointer of environment variable stored in v0

- gets the environment variable length

- copy the data into v180

In addition, we also see the function being used four times at the beginning of the malware.

- The first two iterations will copy the environment variables as mentioned.

- The third iteration will copy a large chunk of code “unk_100A5D8” which be later discovered as the malware’s config.

- The fourth iteration will copy a hardcoded string which will take part in the config decryption part.

unk_100A5D8 array of bytes:

Another function that is interesting is sub_100058F0. This function will copy the data from Src into the variable 156 (internally it will do it using memcpy, the memcpy function is very common in this sample).

We can see that the Src argument is the copied config that was stored in unk_1000A5D8.

Then, the copied content (156) will be sent to the function sub_100019B0 which will deal with the config decryption.

There are two ways to get the config, one of them is very trivial and easy, but where is the fun in that? (we’ll discuss this way at the end of this config section).

Observing the config decryption

If we want to observe some key features of the config decryption mechanism we’ll have to jump inside sub_100019B0.

When we step into the function dynamically, we can see several xor and copying activities, which eventually lead us to a memcpy function that will write the IP addresses.

To observe it, we can just follow in dump on the EDI register.

Then, the malware will check the size of the written content, allocate new memory using Malloc and assign pointer to it.

This small allocation and pointer assign activity will happen in the function 724D7840 (in the followed image).

Then, the first four bytes will be changed to the address that will contain the new buffer of the IP addresses.

As expected, right after passing the function, we can see that the first four bytes have been changed to be a pointer.

If we want to see the array of IP addresses that this pointer points to, do the following:

- Right-click on the pointer

- Follow DWORD in Dump

- Select your preferable dump

Once we click, we could see the array of IP addresses

This activity of writing and assigning a new address for the config will happen several times inside a loop, therefore, to skip it we would want to set a breakpoint right after the loop.

And just like before, we can click on the pointer and follow in dump to see the config.

After getting the config, we can get out of the entire function.

Remember I said there is an easier way to get the config? well, when sub_100019B0 ends, it returns (in the EAX register) the address of the pointer to the config.

To recap, the start of the core function and config extraction can be seen in this pseudo code.

Now that we are more familiar with the malware “maintenance functions”, we can speed things up.

Network function

One of the interesting functions is sub_10001DB0, which appears within the largest loop in the core function. To easily locate this function in your code, search for a sleep() function with 0x5DC0 as an argument.

sub_10001DB0 will be the function that responsible for SquirrelWaffle’s network activity.

Right after entering the function, we encounter the familiar function sub_100019B0, which as we remember also used to decrypt the config.

It also seems to follow a similar pattern of the config extraction:

- sub_10006A20 receive embedded hardcoded content and copy it to he memory.

- Another sub_10006A20 function recieve long hardcoded string.

- sub_100058F0 take the copied content and assign it

- sub_100019B0 take the pointer of the obfuscated content, and the hardcoded string as an arguments.

Because we have already seen this pattern, we remember that if we step over sub_100019B0 we would see some content returned. Interestingly, now the content is a list of C2 domains.

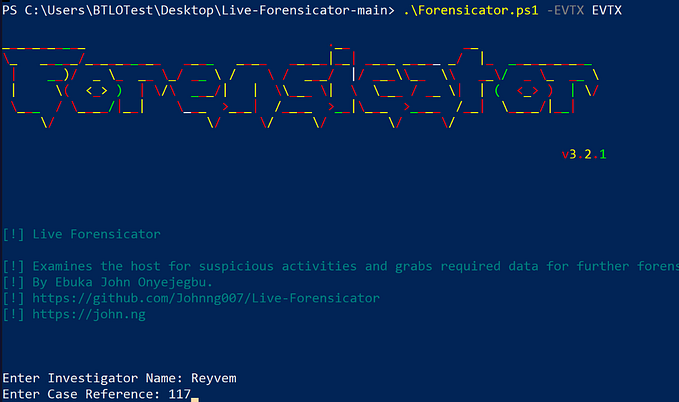

After collecting the C2 domains and IP addresses the malware can finally communicate externally. The communication is done using the classic WS_32 API calls.

The malware first create a socket, send the data using send() and receive information from the C2 using recv().

Once the network function finishes its activity its returns to the core function, then we start to see signs and clues about the content to be download.

Final payload

As mentioned by several security researchers, SquirrelWaffle aims to download the Cobalt-Strike framework. Once downloaded, the SquirrelWaffle store the binary as a .txt file. A maybe possible indication of this activity can be seen in the code with the hardcoded “.txt” strings.

The malware has execution capabilities using the WinExec function. The function itself can be executed in three different locations during the malware execution.

Recap

In this technical analysis, we discussed multiple topics

- SquirrelWaffle dropper and how to unpack it

- SquirrelWaffle core function

- SquirrelWaffle network capabilities as a downloader

- How to observe the SquirrelWaffle list of C2 domains and IP addresses

The entire analysis flow can also be seen in the following graph:

Conclusion and thoughts

In this article, I presented the newly emerged malware downloader SquirrelWaffle. Although SquirrelWaffle is “the new kid on the block” in the cybercrime ecosystem, its dropper already using a very known crypter that was used by other famous malware.

These findings raise the question of whether the threat actor behind SquirrelWaffle is an already known group.

Also, many ransomware attacks have initially started after a successful deployment of the Cobalt-Strike framework, it will be interesting to see how many ransomware attacks will happen because of infiltration by SquirrelWaffle, and which ransomware group will operate with it.

Furthermore, because this malware is new, more features are most likely to be discovered in the near future. It will be interesting to track this malware evolution as times goes on.